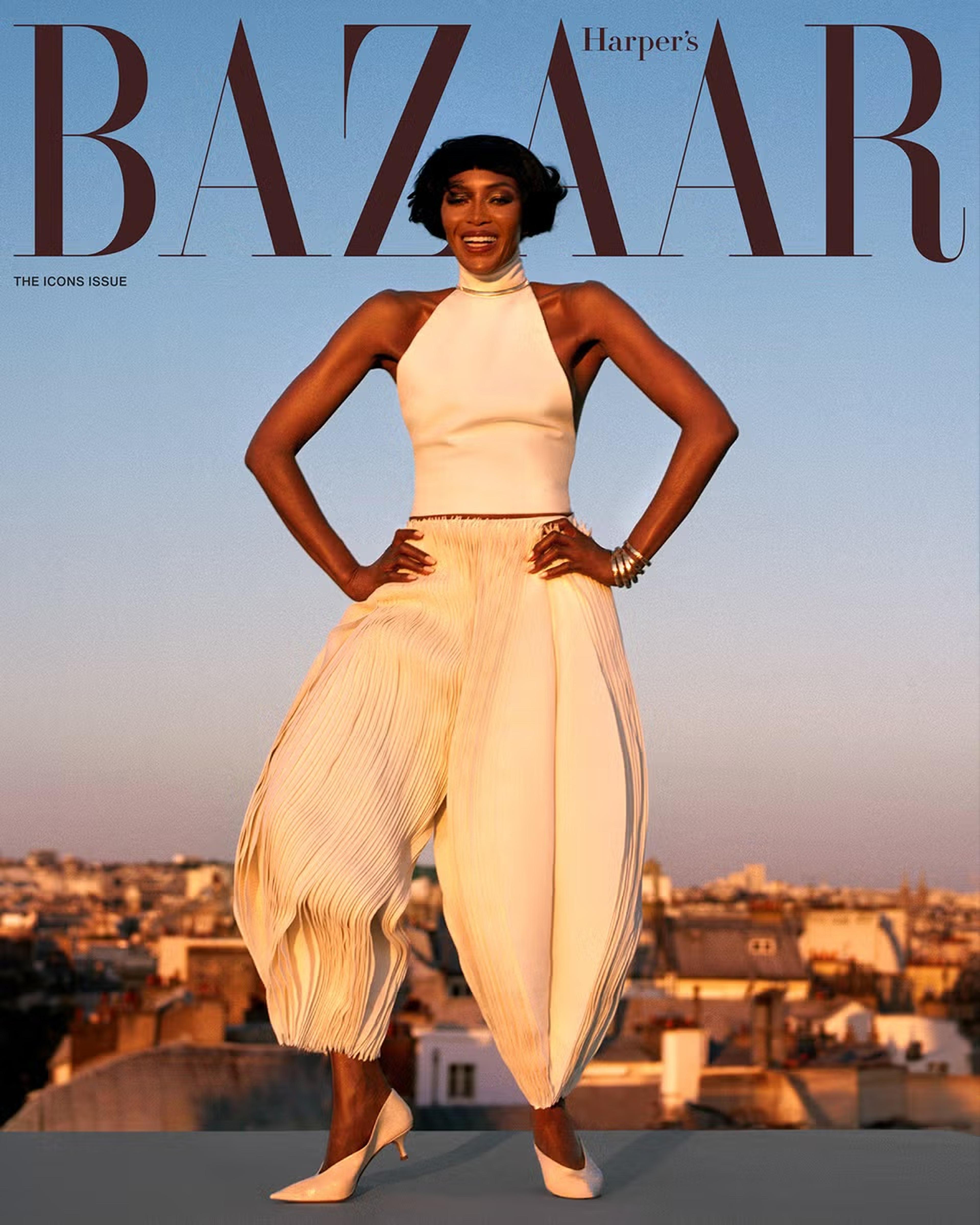

Naomi Campbell Is Like No Other

She broke barriers and rewrote the rules, fell down, got back up, and did it all in nine-inch heels.

As you enter the exhibition “Naomi: In Fashion” at London’s Victoria and Albert Museum, you are greeted by a video montage of Naomi Campbell’s iconic walk down the many runways of her 40-year career: a flirty sashay from baby Naomi at Todd Oldham in the mid-’90s, a moody saunter in a black silk outfit for Isaac Mizrahi from Fall 1997, a dead-serious stomp in a sequined black Saint Laurent tuxedo just a few years ago—all distinctly different, all distinctly Naomi.

A solo V&A exhibition on any one person, particularly during his or her lifetime, is rare and sought-after. (Previous honors have been bestowed upon Alexander McQueen, Frida Kahlo, and David Bowie.) I also observe, quietly, two Black girls, perhaps 16 or 17, who are transfixed, staring closely at the footage and swapping stories about admiring her beauty and “fierceness.” I smile, thinking of my own experience of observing Naomi Campbell from afar at that very age. When I was growing up in London, Campbell’s image and mononym were so inextricably linked with fashion that when I told my West African father, a general practitioner with absolutely no knowledge of fashion, that I had aspirations for a career in the industry, he asked if I wanted to be Naomi.

The exhibition opens with personal images from Campbell’s archive. Baby photos, dance-recital portraits, her childhood ballet shoes, and a candid of a seven-year-old Naomi being tucked into a blanket by Bob Marley (she features in the late musician’s “Is This Love” video) signpost the celebrity to come. There’s one particular image, though, that holds my attention: a jubilant Naomi holding her mother Valerie Morris-Campbell’s waist as they dance and family gathers around the kitchen table in the background. It’s oddly familiar, perhaps because we all have a version of this image in our family photo albums. An image of us deliriously happy, somewhat naive and oblivious to what’s to come. But for me and fellow Black women, images of Campbell have also offered us glimpses of ourselves. Resilient, strong. Misunderstood but always major. She didn’t play the game; she simply chose to change it.

“I didn’t like being the first in a lot of things. Barriers have to be broken. Challenges have to be met,” Campbell tells me of her modeling journey. “I just wanted to do the best work that I could do. [I figured] if I made a decision to be in this business, I would embrace it. I wanted to give it my best because my family definitely did not want me to do this.”

Campbell’s stats read like an MVP’s. There are the 500-plus magazine covers, including one for Time magazine heralding Naomi as a face of the newly minted supermodels, a group that included Linda Evangelista, Christy Turlington, and Cindy Crawford. “They’re the supermodels, and they’re hotter than a curling iron,” the 1991 article quipped. There are the campaigns for as many brands as there are on the floors of Bergdorf’s: Louis Vuitton, Lanvin, Burberry, Valentino, Fendi, and the list goes on.

Then there are the pop-culture moments, some of the most notable (and notorious) of the past 50 years. George Michael’s “Freedom! ’90” music video is etched into the collective consciousness, as is her writhing with Michael Jackson in the “In the Closet” music video two years later. Her fall when she was wearing the nine-inch platform Ghillie heels on Vivienne Westwood’s runway in 1993 garnered so much press, Campbell claimed that other designers later asked her to fall during their shows too. (She refused.) In 2007, when she completed her required community service after pleading guilty to a misdemeanor assault charge, she wore an argent Dolce & Gabbana gown and had Steven Klein pap her from behind the gate. A 2019 video that showed her furiously wiping down her plane seat with disinfectant wipes, which seemed prescient after Covid appeared, went viral on YouTube.

Campbell also has a reputation for what can generously be referred to as a lack of time management. In fact, the scheduling for this cover story is so frantic and delayed that I begin to lose hope we will ever speak. Possibilities of a conversation in New York are dashed, a late-night rendezvous in Sardinia during the Dolce & Gabbana Alta Moda show never materializes, and a walk-through of her Victoria and Albert show is promised and then canceled. Am I exhausted? Yes. But this is the kind of story that befits an icon, that befits Campbell—a supermodel of such epic proportions living up to expectations of being unattainable (and uncontactable). Because being an icon has a multitude of meanings. We, the public, want to lionize or villainize icons, and we don’t forget them. Campbell is singular; in the fleeting cycle of celebrity, stars like hers are hard to fade.

When we do speak, Campbell is on vacation in Ibiza with her two children and a group of friends that includes actresses Eiza González and Michelle Rodriguez. “I haven’t been here in seven years,” she explains as she sits for lunch. “It’s hard to unwind because, yes, I am a workaholic. I will admit that. But you have to do it to help your mind, for your body. You have to reenergize to get inspired, you know what I mean?”

Her respite is well earned. At 54 years old, she has reestablished herself as a catwalk mainstay, but in recent years she has also integrated herself with a new generation of designers, tastemakers, and talents, acting as a mentor and guiding light to an industry in flux—one that is making progress, yes, but still marred by racism, sizeism, and nepotism.

Torishéju Dumi, a British-Nigerian-Brazilian designer based in London, had a Paris Fashion Week debut that was something out of a fashion fairy tale, thanks in part to Campbell’s cosign. “It was so sudden and unexpected,” she says about Campbell opening her Spring 2024 show—Dumi’s first after graduating from Central Saint Martins in 2021—presented in the gilded ballroom at the Shangri-La hotel. “The response was just overwhelming. [Her walking] had an enormous impact on the brand and for me personally, and helped open doors that I never imagined walking through. It’s funny because there’s not a first memory of Naomi Campbell for me. I just remember always seeing her and her being this Black woman that I admire. A true icon.”

Next-generation supermodel Alton Mason considers her his blueprint: “Naomi Campbell is a huge inspiration when it comes to just presence and power as a model,” he recently told Bazaar. “Naomi, Prince, Michael, Tupac. I would say those are my top four.”

“I want them to have control of their image,” Campbell explains of the new vanguard she’s helping reach its potential. “I want them to know that they are a part of something as well. Not just being hired for a job. That they have a story and a journey to share. Everything goes so quickly in our business. I love that in my time, we had real relationships with the designers. It wasn’t just when we were doing shows; we visited each other, we cared, because sometimes it’s kind of lonely. There were many lonely times, but we held each other up. I want to do the same,” she says.

While Cindy, Linda, and Christy all remain part of the public lexicon, it’s Campbell who has consistently endured. She is a collision of beauty, one where art meets commerce: almond eyes, luminous skin, and a body Azzedine Alaïa, the late couturier, once called “like that of a racehorse.” She can sell you Chanel couture and Boss commercialism, all in the same year. She can flit between sexy, coquettish, regality, and demureness if that’s what the assignment calls for. She is racking up her covers (no less than eight so far in 2024, including this one) and campaigns, while her contemporaries have decidedly slowed down.

Fendi artistic director Kim Jones has remained close with Campbell for about 20 years, casting her throughout his time at Fendi, Dior Men’s (which he also helms), and Louis Vuitton, where he famously had Campbell and Kate Moss walk the runway in his farewell menswear show in 2018, in coordinating Monogram trenches. “I met her at a party through Lee [Alexander] McQueen. It was brief, but she was sweet,” Jones recalls. “She is one of a kind. She has the most brilliant sense of humor, and when people ask why she has had such a long career, it’s because she has a special combination of kindness, loyalty, passion, humor, and an ability to adapt to any situation.”

Campbell’s longevity is particularly impressive in an industry where she was one of the “firsts”: the first Black woman to open a Prada show, the first on the cover of French Vogue, the first Black model on the cover of Time. Tremendous praise was welcome, but it also came with “tremendous pressure.”

“People think that you want to be the only one, but it’s not necessarily so,” Campbell explains. “That’s why I wanted to celebrate us in the exhibition—Naomi Sims, Beverly Johnson, Iman, Bethann Hardison, Veronica Webb, Karen Alexander—because they were also before me.”

The exhaustive nature of being one of the first had its effects. She was catnip for the press, which painstakingly documented her highs and lows, but especially her lows: the outbursts, the assault convictions (there were four), and her battle with addiction. This is, sadly, nothing new. So implicit is the association of Black women and “bad behavior,” often levied by public perception and put before any praise, that it universally unites Black women in anguish. If she is a diva, what made her one? Is it who she is or was it her circumstance? Campbell has said she never earned as much money or as many advertising assignments as her white counterparts did. As early as 1991, she said, “I may be considered one of the top models in the world, but in no way do I make the same money as any of them.” Today Campbell says, “A lot of people think, ‘Oh, too strong. She can deal with it.’ To a point. I have feelings just like everyone else.”

“[People say], yes, she’s thrown a phone. Yes, all that,” says activist and former model agent Bethann Hardison, her “American mother,” who has known Campbell since she was 14. “But her self-esteem was always in play from the time she was a teenager. Believe me, the kid has always been determined and self-conscious of who she was, to a point,” Hardison continues, lending some insight into the more intimate side of Campbell. “The fact is that everybody is very taken with her—the outside world, media, people—with the fact that she is Naomi Campbell, just that alone. She’s really one of the few [models] that’s a star that paparazzi care about what happens to her. Thing is, when she does arrive, when it’s time to be on, she has a great personality. And she’s smart as shit.”

Hardison is one of a long line of elders in Campbell’s life who have played guardian to her and her legacy. Her closeness to Azzedine Alaïa is well documented. (She stayed with him in Paris, with her mother’s blessing, when she was 16, and she affectionately called him “Papa.” (Campbell has never met her biological father.) Designer Gianni Versace was a confidant and ally. Vivienne Westwood too. Campbell sang the praises of longtime friend John Galliano in his recent documentary. She made regular trips to Africa to visit Nelson Mandela, who called her his “honorary granddaughter.” Quincy Jones has called her his “other naughty little sister.” The late Clarence Avant, a prominent music executive, was her “Uncle Clarence.” “I’m not a fair-weather friend,” Campbell says. “It’s just not who I am, and I won’t give that back. You grow up together, you are on your journeys together, your journeys are aligned. You build your family outside of your own family.”

Chosen family aside, Campbell made a shocking announcement to the world when she revealed the birth of a daughter in May of 2021 and a son in June of 2023, both delivered via surrogate. They’ve largely been kept out of the spotlight, other than a glimpse of her daughter on the cover of British Vogue, masterminded by her close friend Edward Enninful, who was then the magazine’s editor in chief. She remains understandably scarce on the details (including their names), but she drops into an affectionate rhapsody when she speaks about how they’ve changed her.

“It’s the biggest joy,” she says. “The biggest blessing is to have these two innocent, beautiful souls and for me to be able to be their mother. I learn a lot each day. They’re good kids.” I ask whether jet-setting for jobs has been thwarted. “I definitely don’t take them from New York to London for a two-day shoot. That’s too much, but my kids love to travel. They must have known!” she says, laughing.

Reminiscing about four decades—the designers, the culture, and her own stories—makes for emotional work. “I used to drive by the V&A on the bus and never thought this would ever happen to me. I think it’s even more meaningful because it’s in the country that I was born in. It’s an institution, and I’m just beyond overwhelmed with gratitude,” she says.

Advocacy and philanthropy have been interwoven throughout her career. She’s called for greater model diversity in her work with Hardison’s Diversity Coalition, she was named the global ambassador for the Queen’s Commonwealth Trust in 2021, and she has been honored by amfAR for her 31 years working with the foundation to fuel AIDS research. “My purpose is bigger,” Campbell says. “My purpose is the African continent. My purpose is the emerging creatives. My purpose is to open this up for everybody. There’s so much talent out there that just doesn’t get given that opportunity.”

At the top of the V&A exhibit, you are met with a compendium of some of Campbell’s most memorable looks. That Dolce & Gabbana gown sits next to her Covid-combating outfit from 2020, consisting of a hazmat suit and cashmere Burberry cape. Giggling at the latter, I realize she is one to always embrace the entire narrative: the good, the not so good, the new, the old, the internet, and the analog, and she gives us carte blanche to do the same.

Often, those who are held up as iconic are the ones who are the most complex. They are idolized beyond measure, their mistakes magnified. But the mark of a true icon is how you move through—if and how you are able to evolve. That’s Naomi Campbell: Like a rolling stone, she’s always kept going. She’s welcomed members of a new generation that has been reintroduced to her by way of the wave of ’90s and ’00s nostalgia—and as she explains, she’s as enamored of them as they are of her. “It was so much fun. I love their confidence,” she says of TikTok celebrities like Sabrina Bahsoon, a.k.a. Tube Girl, and Khaby Lame, both of whom she has worked with and she says inspire her. “They’re always asking me what the ’90s were like. I’m just shocked they even know who I am!” That’s hard to believe. As Hardison says, “She will be on the runway when she’s 75. There’ll never be another Naomi!”

Story: Lynette Nylander

Photographs: Malick Bodian

Styling: Carlos Nazario